Table of Contents

Brazil, known for its vast cultural diversity, is a country formed not by one people but by many. The history of Brazil is a patchwork quilt composed of different waves of immigration, each adding unique colors and textures to the national identity. In this article, we will explore how these waves of immigrants shaped Brazilian culture, creating a rich and diverse social fabric.

The Portuguese Colonization

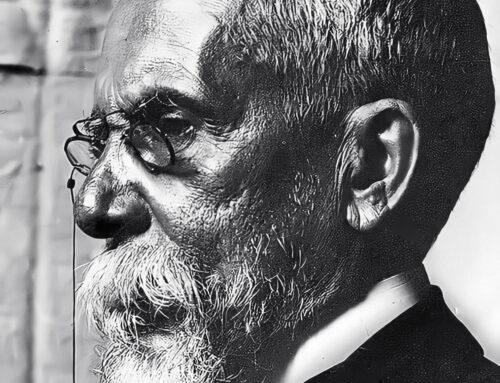

p-12-1

Oscar Pereira da Silva (1922), Historisches Nationalmuseum in Rio de Janeiro

The history of immigration in Brazil begins on April 22, 1500, when the land of Vera Cruz, which today corresponds to Brazil, was claimed by the Portuguese Empire with the arrival of the fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral at Porto Seguro. European colonization effectively began in 1534 when D. João III divided the territory into fourteen hereditary captaincies, granted to twelve donatários (donees). These donees were responsible for exploring the land’s resources, populating, protecting, and establishing the cultivation of sugar cane, with their rights and duties regulated by foral charters, with the Foral of the Captaincy of Pernambuco serving as a model for the other captaincies.

Records of Portuguese immigration intensified in the 18th century and became more regular from the 19th century onwards. In the first two centuries of colonization, about 100,000 Portuguese came to Brazil, with an annual average of 500 immigrants. This number increased significantly in the following century, with 600,000 immigrants recorded and an annual average of 10,000. The peak of migration occurred in the first half of the 20th century, between 1901 and 1930, when the annual average exceeded 25,000. The Portuguese influence is evident in the language, Catholicism, and the strong literary tradition that became pillars of Brazilian culture.

The African Diaspora

On the American continent, Brazil was the country that imported the most enslaved Africans. Between the 16th and mid-19th centuries, about 4 million African men, women, and children were brought to Brazil, representing more than a third of the entire transatlantic slave trade. This chapter of Brazilian history, though painful, left an indelible mark on national culture. Upon boarding the slave ships, peoples like the Jejes, Yorubas, and many others were forced to leave behind their history, customs, and religions, being identified based on their ports of embarkation or regions of origin, forming new identities such as Bantus, Nagôs, and Minas. During the diaspora, new identity configurations emerged, including Creoles (slaves born in the Americas) and, later, Afro-Brazilians.

The African influence in Brazil is profound and comprehensive, especially in music, cuisine, and Afro-Brazilian religions. Samba, for example, has roots in African traditions and is today a symbol of Brazilian national identity. Similarly, dishes like feijoada and religious rituals like candomblé and umbanda are living testimonies of the African heritage in Brazil.

The Italians and the Transformation of the South

In the second half of the 19th century, Brazil became the destination for many Europeans, with a special emphasis on Italians. Between 1875 and 1900, approximately 577,000 Italians arrived in Brazil, representing the majority of European immigrants who disembarked in the country during that period. They settled mainly in São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul, deeply influencing the culture of these regions.

Italian immigration occurred in two ways: spontaneous and organized. Spontaneous immigration began in the first half of the 19th century with families and individuals, such as priests, musicians, and artists, seeking new opportunities in Brazilian cities. Organized immigration was encouraged by laws and societies that offered government subsidies, free passages, reception at the port, accommodation, and transportation to the coffee plantations. Between 1874 and 1889, about 320,000 Italians arrived in Brazil, attracted by the promise of a new beginning in the “paese della cuccagna” (land of plenty).

The Italians brought their culinary traditions, such as pizza and wine, and festivals like the grape festival, enriching Brazil’s cultural diversity. Cities like São Paulo and Curitiba still preserve a strong Italian influence, reflected in gastronomy, music, and cultural celebrations.

The Japanese Influence

The Japanese began arriving in Brazil in the early 20th century, mainly settling in the state of São Paulo. The first group of Japanese immigrants arrived in 1908 aboard the ship Kasato Maru. Diplomatic relations between Brazil and Japan had already been established in 1895 with the Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation. Between 1917 and 1940, about 164,000 Japanese immigrated to Brazil, with the majority arriving between 1920 and 1930.

The Japanese community in Brazil, known as Nikkei, is the largest outside Japan, with approximately 2.1 million people. They brought advanced agricultural techniques and a strong work ethic that transformed agriculture in regions like the Vale do Ribeira. Additionally, Japanese culture influenced Brazilian cuisine with the introduction of dishes such as sushi and tempura, which are now widely enjoyed throughout the country.

Other Waves of Immigration

Besides these groups, many others also contributed to Brazil’s cultural diversity. The Germans in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, the Lebanese and Syrians, mainly in commerce, and the Spaniards, who spread throughout the country, are just a few examples. Each group brought a bit of their own culture, which was absorbed and reinterpreted in Brazil.

Today’s Brazil is a vibrant country, full of colors, flavors, and sounds that are the direct result of centuries of immigration. Each immigrant group left its indelible mark on Brazilian culture, making it one of the most diverse in the world. Learning about these influences is to understand a bit more about the rich tapestry that makes up Brazil.

This panorama shows how the Brazilian nation is truly a land of many, where different cultures meet and intertwine, creating a unique cultural mosaic in the world. Celebrating this diversity is undoubtedly celebrating the essence of Brazil.

Sources: